Until recently, not many Swedish words were known outside the country, with just a few of its words adopted elsewhere, most of them fairly unexciting: ‘orienteering’, ‘ombudsman’, ‘smorgasbord’.

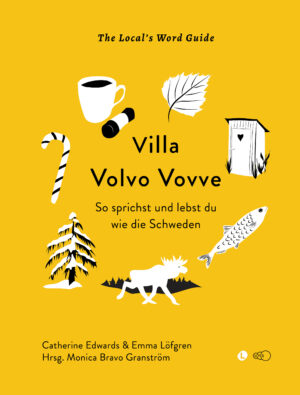

But then a trend for Scandinavian culture swept the globe, boosted by surveys showing their populations to be the world’s happiest, most equal, or boasting the best quality of life. Two words in particular were catapulted to linguistic stardom: fika and lagom, roughly ‘coffee break’ and ‘just the right amount’. Magazine articles and books debate whether the words themselves give us an insight into some ‘Swedish secret’ of how to live.

Perhaps they did. Perhaps words from other languages open up for different ways of seeing and interacting with the world. Perhaps Swedes can inspire the world to take it more easy and hang out over some hot drink. And by giving things a name they are validated.

When arriving to Sweden, this is what many internationals have in mind. They’ve come for the work-life balance, access to nature, affordable childcare, and so on. But as they stay a while, Sweden becomes more complex. It’s a land of much more than Ikea and moose and cinnamon rolls. Sometimes this leads to the Good Sweden Bad Sweden debate, that is, Sweden is not the advertised utopia but a hellish place where all sorts of nasty [insert ideology of choice] is covered up by the media.

Surely, this is not the greyscale we should all aim for. Sweden is neither the happy land of lagom nor the headquarters of some anti-humanitarian cult. Sweden is a country like all others, as unique and quirky as all others. And if we leave the good and bad discussion behind, there’s plenty of opportunity to explore this society and culture.

This is probably why The Local’s article series Swedish Word of the Day has been so successful with its readers. It gives insights into the world of Sweden, how people organise their lives, what they find joy in and how they express themselves. Word of the Day brings up words and concepts that go beyond the clichés and stereotypes.

Swedish has much more to offer than ‘fika’ and ‘lagom’, Swedish is, for example, ‘nja’, the yes-no hybrid that the locals use in order to be nice to each other whilst declining and offer or disagreeing with them. Swedish gave us the verb ‘orka’, to have the physical or mental energy to do something, and which is almost always used negated. Because human life is so much about not being able to live up to all the expectations and demands put on us.

Swedish is the language of ‘puss’, the type of kiss that is loving but not sexual, and ‘rolig’, that used to mean calm but now means fun, or funny. Swedish gives us ‘tråkig’ that can either mean boring or sad, which means you need to rely on contextual clues when someone expresses their sympathies when your pet has died. Swedish is ‘semester’ that doesn’t mean what it seems to mean, and ‘gift’ that is somehow a gift, and only sometimes one that keeps on giving. Swedish gives us the poetic ‘mashed snow’ to describe words that lack meaning, and the ‘age of defiance’ that could refer to the terrible twos but has the potential to go on for ever. Swedish is a language of long words, like ‘surströmmingspremiär’ and ‘påskrispynt’ and ‘realisationsvinstbeskattning’, but also a language of short words, such as ‘a’ and ‘å’ and ‘ö’.

In Villa Volvo Vovve, you can read “Swedes are often people of few words”, but this doesn’t mean the Swedish language is.

Villa Volvo Vovve will be published on October 28, 2021, but is already available for pre-order.