Working mothers

I often receive emails from people wanting to relocate to Sweden, asking what the situation is for working mothers. Now, I should be able to share some personal experiences here, as I work, and I have two children. That would, from many perspectives, make me a working mother, but I don’t identify with one. I think very few Swedish mothers do, although most of them work outside the home.

Swedish parenting policy is fiercely marketed by the Swedish Institute, and although far from perfect (in my opinion), something to be very proud of. When a child is born, their parents are given 480 days of paid parental leave, funded by the state, to share between them. We don’t talk about ‘maternity leave’ or even ‘paternity leave’, it is ‘parental leave’. I am not primarily a mother, but a parent, creating a sense — and reality — of shared responsibility.

The reason women work although they have children may be interpreted as a strong feminist agenda, but, arguably, there are several and stronger currents that have made this reality. Sweden is a small country, or rather a large country with a small population. There are, simply enough, not enough people to make up the workforce necessary to keep the country running. If half the working-age population stay at home because they are women or mothers, there’s not enough people to do the job.

So, the concept of a working mother is as foreign as a working father, to me, and to many other Swedes. We are parents. And we work. But none of these is more remarkable than being human, so not something we talk about.

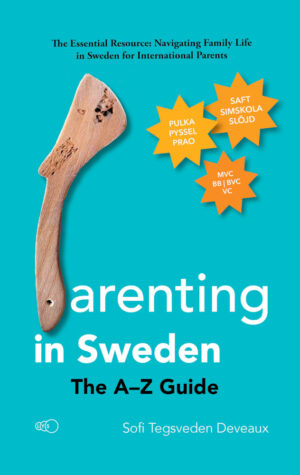

DIY

I learnt of this term when living in the UK. Apparently it was a big thing to do it yourself. But who else would do it? I am brought up not only to mend what is broken, but to construct what is needed. Not only did we redecorate our house to make it a home and build a shed or two, but also school fosters this crafty attitude. From the age of eight or nine, Swedish children are taught slöjd, inadequately translated as ‘craft’, in two subjects: metal and woodwork as well as textiles; the latter including sewing, knitting, crocheting and embroidery. I never excelled, but I can confidently make some basic clothes for myself (if needed), and household textiles such as curtains, pillow cases and tote bags. Likewise, I can use some basic tools to build a small piece of furniture, or set up a fence. I know how to use a needle, a sewing machine, a screwdriver and an axe. Most Swedes, all ages and genders included, do.

DIY in Sweden is not a hobby, it is not a chosen path or a lifestyle. It is a way of getting things done.

Wild swimming

In the afternoons, I pack my swimming costume and a towel and walk to the nearest lake. I’m just outside the centre of Stockholm, but not 20 minutes away from lake Mälaren, where I can easily access beautiful, clean albeit freezing water.

I do this from April and May and onwards, until I start shop for Christmas decorations. Perhaps not representative of most people, who take a more sensible approach and enjoy this activity for one or two months each summer. But Swedes swim everywhere and all the time. By one of the several thousand beaches and designated swimming spots that you find all over the country.

We are a swimming nation. And I’m not talking pools, lidos or anything pre-arranged. No life-guards in sight, perhaps no people in sight. You may think the climate would forbid it, but in fact it is the very reason. A day suitable for swimming is a victory, another way of denying the Arctic conditions of our home.

A few months ago, a newspaper article highlighted the new trend of ‘wild swimming’. It was mocked on social media. There is no wild swimming to explore in Sweden. It is already here. It’s called att bada — ‘to bathe’.

Sofi Tegsveden Deveaux

Publisher & Editor