“Get me a chocolate muffins,” my Swedish friend says. “I’ll fix a taxi.”

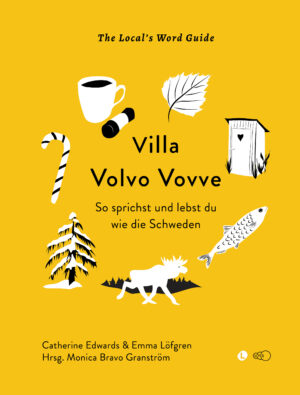

As I stroll into the bakery, I realise that a novice to Sweden might be confused at this point. What exactly did my friend order? How many oversized cupcakes is “a muffins”? The answer is one. Swedes often borrow English words but fail to read the instructions, leading to the plural and singular forms, with the “s” and without, being used interchangeably. One wraps. Eight muffins. A scones. One muffins. One wrap.

As I stroll into the bakery, I realise that a novice to Sweden might be confused at this point. What exactly did my friend order? How many oversized cupcakes is “a muffins”? The answer is one. Swedes often borrow English words but fail to read the instructions, leading to the plural and singular forms, with the “s” and without, being used interchangeably. One wraps. Eight muffins. A scones. One muffins. One wrap.

Swedes don’t even notice when they do this, but for the English speaker it can be like nails down a blackboard. On the other hand, many Swedish singular nouns sound plural to us anglophones because of the s sound at the end. Keps. Räls. Or even kex.

I leave the bakery, bag in hand, and see my friend standing by a taxi, waving me over. I stare at the taxi, and its “Two Dices” logo, and grip my bag of bakery products a little tighter.

“What’s wrong?” my friend says. “I thought you liked dices.”

Can You English?

As an Irish immigrant arriving in Sweden, the first thing that strikes you (after the gorgeous nature, fantastic teeth, and bizzare love for dairy products) is the English. Not only is it liberally sprinkled amongst Swedish words in conversation, but it’s also visible on signs, in shops, in company names, and most of all, in advertising.

The second thing that strikes you is how often English advertising copy makes absolutely no sense.

I call it the Swedish Dilemma — excellent English skills combined with an over-confident belief that your command of the language is so good it does not need to be checked by a native speaker, ever. Swedes therefore take it upon themselves to write advertising texts (known in the biz as “copy”) in English, and often it’s just plain wrong. It glares at us native speakers from billboards. It screams at us from magazine pages. It barks at us from shop windows like annoying dogs as we pass.

Because in Sweden, bad English copy, like weird pizza, is everywhere.

Every year a study is widely and proudly shared on Swedish social media. In the 2019 version, entitled “Top 10 countries with the best English”, Sweden took second place, just ahead of Norway (which pleased the Swedes hugely, since beating Norway at anything is cause for national celebration). However, I find the title reflective of the whole problem. Don’t they mean “Top 10 countries with the best English as a second language?” Because otherwise the UK, Jamaica, Tonga, Australia, Singapore and Ireland should be on that list too, and they’re not. I don’t think I saw any Swedes react to that. Perhaps it was just understood. Or perhaps Swedes just kind of forget that English is actually spoken in other places, for real, and that it’s not just a delightful topping with which to liven up your own linguistic ice-cream.

It can’t be denied that, here in Sweden, English is seen as “cool”. Maybe because Swedish, with its ten million speakers, can feel tiny when compared to many other languages. Or because the USA and its culture has been hugely popular here for decades. Either way, there’s a widespread belief that your shop, bar, cafe or Reiki studio becomes at least twice as exciting if given an English name. Olssons Vinbar? Try Big O Wine Bar. Södermalms Hund och Katt? Sorry, I think you meant South City Furry Friends. And good luck finding a tattoo parlour in Stockholm that isn’t named something like Fleshy Canvas or An Oh With Two Pricks.

I have never stopped noticing these examples of questionable English. After a few years, I even started photographing them, as a way to amuse myself, or to share a laugh with my anglophone friends down the pub. But soon, as I nestled my way deeper into the culture, I started to realise that these odd snippets of English were more than just funny distractions. They were in fact teaching me about the Swedes, about how they think, about how their society works. They were a part of the whole process.

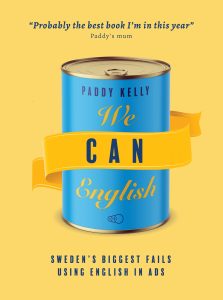

And they lead me here, to this collection of insights now a book. The title is We Can English. And you can find it here.