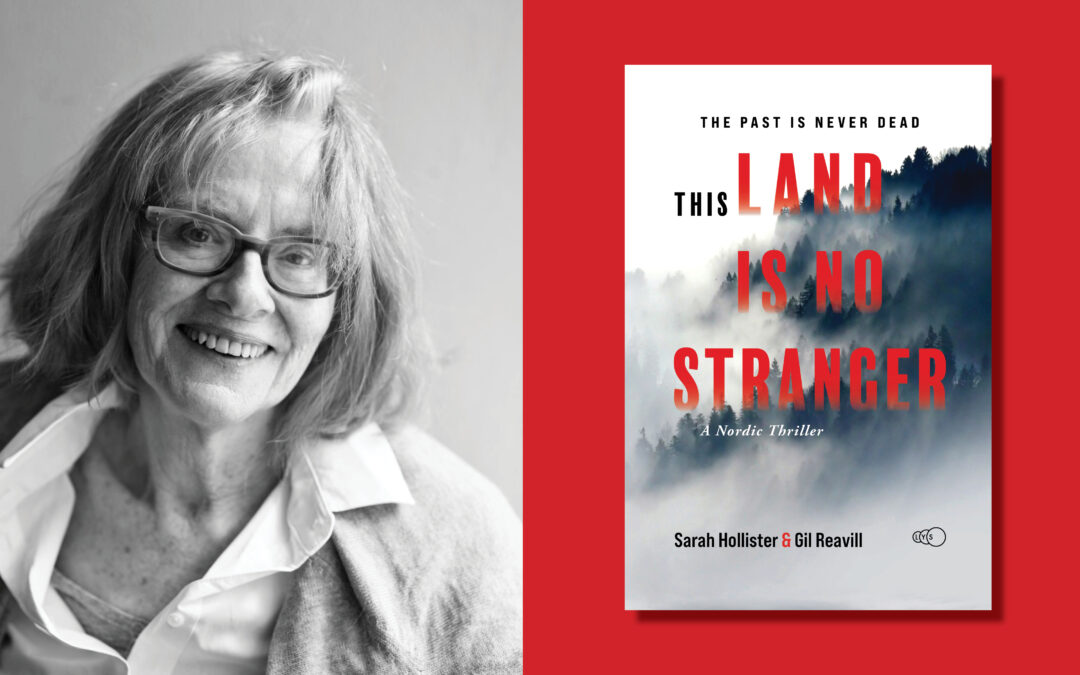

Sarah Hollister co-wrote the crime novel This Land is no Stranger together with New York-based Gil Reavill. In this interview, she tells us where she found the inspiration for their Nordic Noir novel and how the idea evolved over time

An interview by the LYS editorial team

You have previously told me that the novel that eventually became This Land is no Stranger came about a very long time ago. Where did the idea come from and how has it evolved over time?

The inspiration for the Roma characters in our book came on a snowy night in Stockholm years ago when I came upon a small band of women draped in heavy blankets, talking and laughing despite the cold winds and snow. One of the women sat leaning up against a store window, only her head visible, a little like a queen bee. The scene is sharp in my mind, a strange tableau lit from behind by the bright lights of the store. It was 2007 or 2008 following the EU vote to include Romania and BuIgaria. As an American, I still described them as “gypsies” and had many of the same stereotypes as the rest of the world at the time. I felt a strong need to write about the Roma, to tell their story. Though I began writing a mystery novel about the disappearance of young Roma women from the streets of Stockholm, I abandoned it and moved on to other projects. Years later I had an email from Gil Reavill, my co-author, saying he had an idea for a Nordic noir revolving around a New York City woman detective who comes to Sweden to track down a serial killer and would I like to be part of it. We began exploring how to mesh the two threads, the disappearing Roma women and the New York detective, into one story. Over time, the detective became a Swedish American, Veronika Brand, who travels to Sweden, seeking to unravel a family mystery that began in 1940. While in Sweden, she becomes involved in the disappearances of young Roma women.

Why do a Nordic noir novel instead of some other genre?

I was given an assignment to read Henning Mankell’s Mördare utan ansikte (Faceless Killers) from one of my Swedish language teachers. I was captivated, not only by his detective, the morose Kurt Wallander, but also by his minimalist writing style. He is an elegant writer both in Swedish and English. I felt inspired to turn the page, to find out what happened next. The aspect of social critique, a staple of the genre, also greatly appeals to me. The more I discovered about writers of Nordic noir, those like Sjövall and Wahlöö who preceded Henning Mankell, the more I appreciated the Nordic noir premise of highlighting social injustice in society.

Does the content of the book reflect reality, and if so, in what ways?

Well, first of all it’s fiction, but yes in certain ways it addresses reality. The Roma, for example—those who began arriving in 2007-08 from Romania and Bulgaria. They remain mendicants on the streets throughout Sweden, often positioned in front of a grocery store. Community groups offer help, but the Swedish government has not begun a serious process of integration. On the other hand, it should be mentioned that the Swedish Roma, whose ancestors arrived here 500 years ago, organized in the 1950s, demanding civil rights, housing and education for their children. Today they can be found in academia, business, cultural organizations and parliament.

Another Swedish reality reflected in the book is wealth and well being. This country is not the depressed image—the socialist and sad one—portrayed in certain media reports on Sweden. Capitalism flourishes in Sweden. The trains run on time, health care is almost free, day care is subsidized by the government so both parents can work if they so desire, education is also free and so on. Taxes are high but the return is substantial, you get what you pay for. And yet, a gap is growing between those who have and those who have less. In 2018 the far right party Sverigedemocraterna captured 17% of parliament seats. There is divisive fear and racism here just as there is everywhere and this is reflected in the book.

You have co-written the book with Gil Reavill, who has been based in the US the whole time and who has limited experience of Sweden. In what ways do you two regard the country differently?

My experience is the daily exposure to the nitty gritty of life in Sweden, paying bills, riding the subway, becoming aware that culturally there is a vast difference between Sweden and the U.S. Gil sees the country from afar through the lens of history and the media. The media, in particular, cannot be depended on to accurately reflect the society here. But that was part of our collaborative process, discussions about how the media presents Sweden and what the reality is. Gil is an avid researcher, besides being an innovative outside-the-box writer and thinker. And again, it’s fiction.

A large proportion of the story takes place in the province of Härjedalen. Could you tell us about your relationship with this region?

As a member of the Dramatikerförbund (The Swedish drama guild), I was eligible to apply for the Henning Mankell writer’s residence, located just outside the town of Sveg in Härjedalen. I have been fortunate to visit the residence several times together with my partner, Gunnar (families are also welcome). I fell in love with the raw and beautiful nature up there, especially during the frozen winter. Henning Mankell, who spent his childhood in Sveg, bought the two-story residence house on the side of a mountain and gifted it to the two writer’s guilds in Sweden. The landscape of the book, often described as lonely, reflects this sparsely populated region of northwest Sweden.

The main character, Veronika Brand, visits Sweden from NYC. She sees herself as an outsider and compares a New Yorker in Sweden to a bull in a china shop. Do you think this reflects a stereotype or reality? Is there such a thing as a national psyche?

After twenty years of life in New York, I moved to Sweden. I can testify to the bull in a china shop theory. New York is a city where everyone talks to anyone, any time in any situation. Arriving in Sweden I initially continued my New York habit of chatting to strangers. This did/does not work here. One is often met by silence and a suspicious glance. I have learned restraint living here. That is my reality. Being excused for my blunders on account of being an American is also a reality. Stereotypes often reflect an aspect of reality, so I would say it depends on the enormity of the blunder.

The national psyche of Sweden. I believe it can be found in one word, lagom, never too much, never too little, just right. Though that is changing. Ostentatious displays of wealth are on the rise.

In what ways did the book change during the editing process, and how do you feel about that?

The story became more fluent and flowing, the characters deepened and became more authentic. Having editors outside the process and thus objective query our assumptions helped throw new light on the writing and bring more cohesion to the story. I feel grateful.